News -

Mountains of magic in Ladakh - The Independant

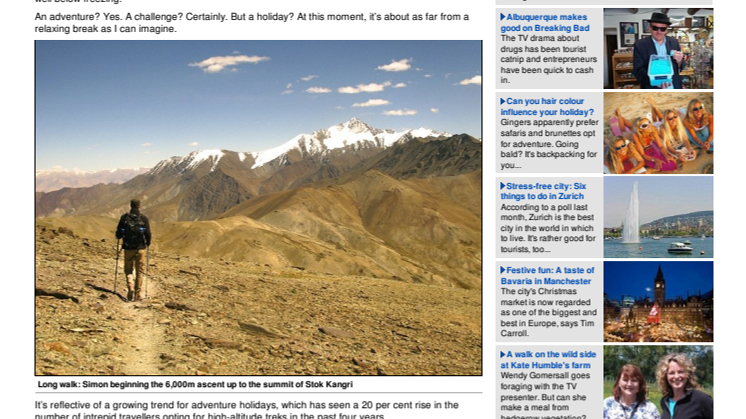

Crossing the Himalayas from the Indian plains to the mountain region of Ladak his a bone-shaking 22-hour minibus ride,through snow and blizzards, over four of the world’s highest passes. The last and highest,Taglang la, is a breathtaking 5,328m above sea level and the second-highest pass in the world that you can drive over (after Khardung la, 5,602m, in northern Ladakh). From there, I hope to see Ladakh’s other-worldly pink deserts. But when we get there there’s dense cloud and freezing winds and it’s all I can do to hop out, shivering, and take a couple of photos of the cairns, prayer flags and Buddhist stupas marking the top.It’s only when the minibus descends that I catch my first glimpse of Ladakh’s magical landscape.

We drive through pouring rain along a spectacular gorge, between jagged maroon-hued mountains etched into surreal rock formations. Even the puddles are pink. On rocks and hills and huddled invalleys between dazzling green fields are whitewashed buildings with slanted window frames painted in brilliant colours. Lines of rain-sodden prayer flags hang limply from flat roofs.For me, this is a homecoming. I spent a couple of months here in 1981 in an inn run by an Englishman who was installing solar heating in Ladakhi homes (despite the rain that marked this arrival,solar heating makes perfect sense: Ladakh normally enjoys intensely bright sunshine nearly all year around). I spoke enough Tibetan (which is close to the Ladakhi language) to communicate a little, and I spent my time visiting temples and monasteries and painting pictures of the lunar landscape. I used to sit high on the hillside and listen to the sound of unearthly whistling rising through the still air as women in long black dresses and stove-pipe hats worked in the barley fields below.

In those days, there were few westerners – and fewer cars. Ladakh had only been open to tourists for seven years. Bordering on China and close to Pakistan, it is strategically sensitive. There had been wars with China and Pakistan and fighting in Kashmir and it was only when things quietened down in 1974 that the Indian government decided to open the area to overland travel, though it was so remote and difficult to get to that few travellers considered going. It can still only be reached byroad between June and September, after which the passes are submerged deep under snow.Roughly the size of Scotland, Ladakh is part of the northern Indian state of Jammu and Kashmir,and has a population of less than 300,000. It was the crossroads of the ancient trade routes from South Asia and until the end of the 19th century,mule trains carrying shawls and spices made the journey from Amritsar through Ladakh to Yark and in China. This haven of Tibetan culture – Ladakh’s people are a mix of Tibetan and Indo Aryan– it became part of independent India in 1948.

More than 30 years after my first visit, this time I’ve come on an organised tour. There are eight in our group including our leader, Bhupesh, a charming,ebullient young man from Darjeeling. Our journey began in Amritsar, in 44C heat. We travelled 150km north east to McLeod Ganj, where the Dalai Lama lives, climbing ever higher to Manali, from where we made the three-day journey across the Himalayas to Ladakh. An epic adventure – and now we’ve arrived in Ladakh, the best is yet to come.

I awake to brilliant blue skies and a vista of snow covered crags, dazzling white, behind the barren purple and mauve mountains that edge the valley.I’m thrilled to be back in this ravishing landscape with its doll’s-house buildings, fluttering prayer flags and white stupas perched everywhere.I set off in search of my old home but the town has grown beyond recognition. It’s full of stalls and shops – Tibetan refugees selling prayer wheels and turquoise and coral jewellery alongside Kashmirimerchants offering pashminas: “fixed price, no bargaining”. The palace looms above the city, with sloping, buttressed walls and overhanging wooden balconies. In 1981, it was a crumbling ruin, now it’s been restored. There are steps and a footpath leading up to it and a road along which Indian tourists cruise in their SUVs. I set off briskly but I’m soon panting. Leh is in a valley but it’s still set at 3,524m above sea level. I reach the entrance with its carved lion heads and poke around the maze of dark rooms,skirting the occasional hole in the floor. Only the throne room, painted with tigers and Buddhist symbols, retains some ancient grandeur.

I take a stroll north of the city, which in 1981 was full of barley fields. Now it’s bustling with building work as hotels and guesthouses spring up. The Dalai Lama is due to visit in July and the city is expecting an influx of 100,000 visitors. I pass a woman with long plaits wearing a black home spun dress, fingering prayer beads and humming quietly. She smiles and greets me with,“Julay”, the traditional greeting, which means“hello” and “goodbye” as well as “thank you”.The next day we drive to the monastery complex of Thiksey, an hour south of Leh. Here, whitewashed temples sit on the hill like fortresses. Ourguide is a young lama (a teacher, usually a monk)called Jamyang. He wears trainers, a burgundy T-shirt that matches his robes and a slightly bemused look. We are as exotic to him as he is to us.

We climb from temple to temple, admiring the altars and hangings, the burning incense and butterlamps, and the beautifully executed thankas– paintings of deities that follow an iconography as precise as medieval western religious paintings.Jamyang explains the different deities: not just serene Buddhas but fierce manifestations festooned with skulls. In one of the temples there is a beautiful golden image, two storeys high, of Maitreya, the future Buddha who is to come.

We walk through fields lined with poplars and willow trees to the fortress and monastery at Shey,once the king’s summer palace. “Every year more visitors come, much is changing,” says LamaJamyang. “Small changes are good, big changesbad. There are more and more hotels; too many cars. One day, no one will come any more because Ladakh has changed so much.” There has certainly been a boom in tourism, particularly in the past 10 years, with a lot of investment by the Indian government and a huge boost in domestic tourists.It’s hard to find consistent statistics but around 8,000 tourists visited in 2002, while by the end of 2013 some 137,000 had passed through.

We spend the following day at the Hemis festival,a day-long dance extravaganza. Actually, says Jamyang, it should properly be called a ceremony.The real purpose is not to entertain but to makerain come, the fi elds grow and the work of the temple prosper. Most monasteries hold a festival every year . At Hemis, crowds have gathered. Westerners with long-lensed cameras rub shoulders with locals. Boy monks run out, red robes flying,and squash into a corner of the courtyard. Then horns sound out , drums beat, cymbals clash, trumpets blare and masked dancers emerge, whirling in slow motion, balancing on one clogged foot,then the other, in a mesmerising ritual.

Suddenly the sky clouds over and hail falls, then sleet, unusual since Ladakh is said to get no more rainfall than the Sahara . After a respectful pause most of the audience flees, though the dancing goes on until evening. Jamyang does no more than pull his robe over his head. It’s good luck when i trains, he says. The ceremony will be successful.We drive for fi ve hours north west to the village of Alchi, home to four monasteries which house Ladakh’s most treasured Buddhist frescos dating from the 11th century. It’s an idyllic place beside a turquoise river with emerald-green trees on the banks.Outside my window are sheer rock faces, purplish brown. Jamyang may be a lama but he’s still 26 years old. He scrambles up a dusty mountain slope and runs straight down, red robes flying.

In the valley, women with long plaits and stove pipe hats work the fields. One waves , rushes over, beaming, and thrusts a bunch of newly picked pea pods into my hands. The country is changing, but despite the new hotels and the influx of tourists,for the time being at least, there’s enough of the old Ladakh left to make it as enchanting as ever.

Topics

- Vacation

Categories

- what the papers say...

- india

- trekking

- walking

- walking holidays