Blogginlägg -

Unusual Encounters in the Field: Researchers and Local Governments Fostering Child-Focused Cities Agenda

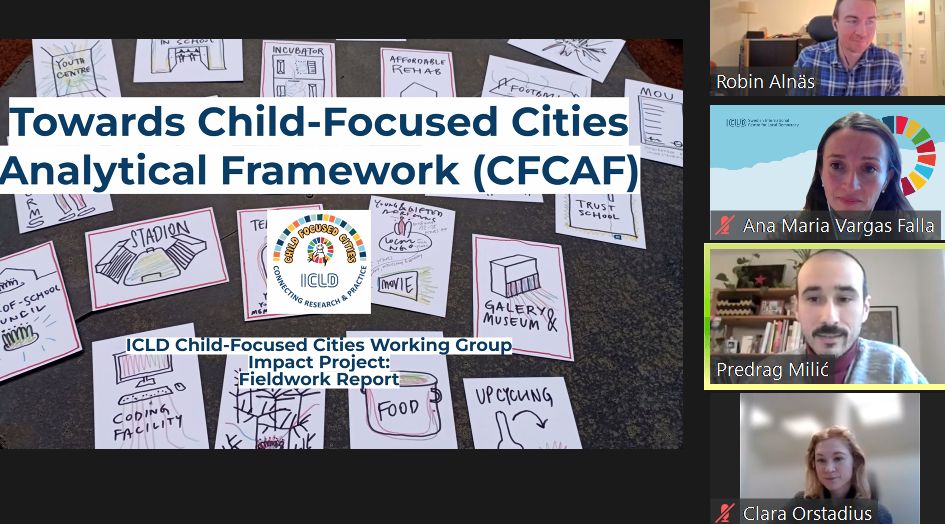

The ICLD Impact Research Project Let's get together and make change: Towards the Child-Focused Cities Analytical Framework (CFCAF) offered a platform for international scholars and local governments to discuss childhood and youthhood matters. This unusual and exciting encounter in the field laid a foundation for the development of a new Analytical Framework - a tool that could foster the Child-Focused Cities Agenda worldwide.

Reflections by the research team

There is plenty of focus on child-friendly cities - but friendly still reflects a top-down narrative. We wanted to go beyond that, toward child-focused, which puts the actual participation and perspectives of children and youth in the center. The novelty of the CFCAF project was in co-creation between the researchers, practitioners, decision-makers and local government officials, using a participatory and perspective-shift approach. For example, shifting perspectives on childhoodenabled us to recognize society-wide barriers and opportunities for children to be considered in policymaking as a vulnerable social group. Bringing together experts from multiple continents and disciplines (such as architects, urban planners, social workers and lawyers) created a mutual learning flow that illuminated the obstacles, opportunities, and capacities of those involved in fostering the Child-Focused Cities Agenda. It also showed why this cause is worthy of much more attention.

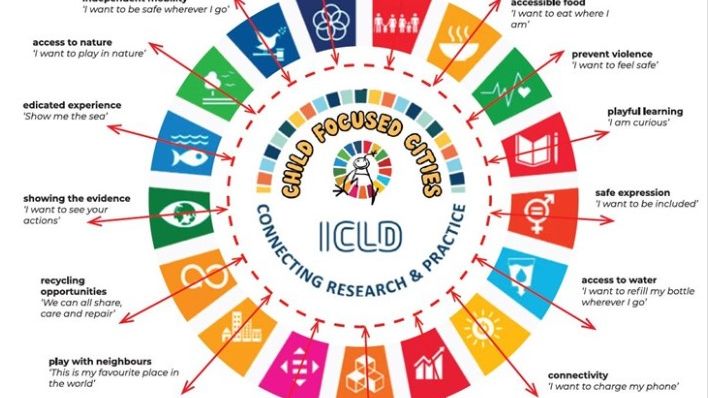

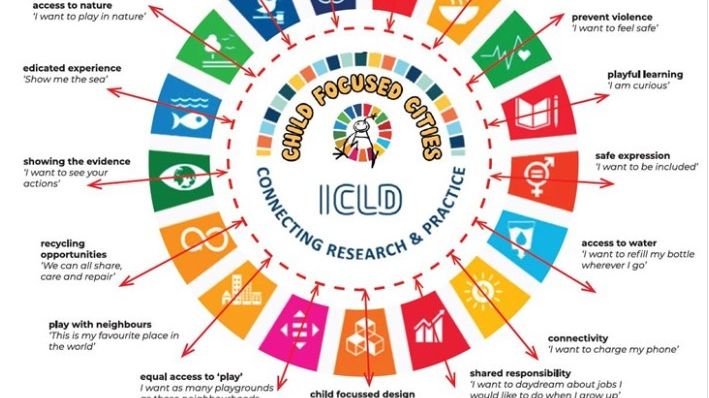

Our international group of researchers started with the idea to help ‘spatialise’ the way Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) respond to the needs, interests, expectations and capacities of children and youth to participate in local (public) affairs. In the field, we noticed a lack of capacity to connect local approaches and global political instruments like the SDG. Specifically, in spite of the general recognition of the SDGs, our encounters did not illuminate targeted responses to individual goals, nor a clear understanding of how it would be seen from a children's perspective. However, we witnessed incredible generosity, openness and commitment from individuals, who regardless of the very weak structures of support remain committed to improving context-specific approaches to child and youth inclusion.

Thus, the field encounters opened a door for participatory data collection, knowledge sharing, and sustainable empowerment of practitioners and officials on the ground, through learning from each other and good practices from other local authorities. This approach of translating and linking global and local perspectives enables practitioners, researchers, and decision-makers to make sense of the available instruments. It allows them to identify gaps and fill these by developing new local responses. Also, it provides communities with relevant data and knowledge to continue in locally driven advocacy and holding local authorities accountable.

We found that the Child-Focused Cities Agenda could be a powerful way to create social change that goes beyond and avoids the pitfalls of child-friendly ideas. The Analytical Tool could be a relational object that can help us mediate different knowledge production traditions – top-down and bottom-up – while incentivising cross-sectoral collaboration. It could be a powerful tool for improving the position of children and young people, through its capacity to be both a lens through which to look at the world and a strategic tool by which to drive action with children. It is about trying to understand the structural and contextual dimensions of childhood in order to alter it, to enable children and young people to take part in societal matters.

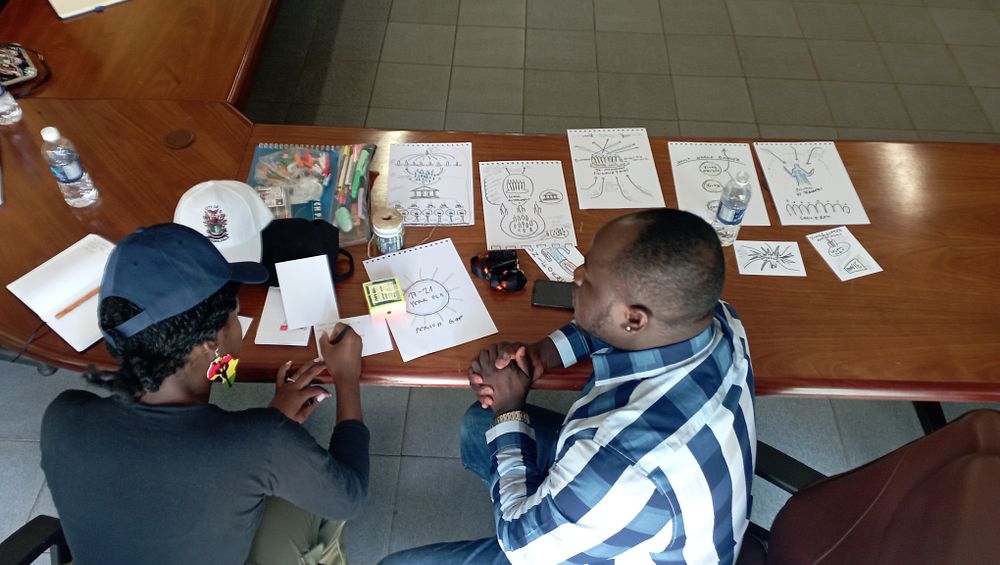

Our team conceptualized the Child-focused Cities Agenda as a relational object – the Anlaytic Framework – from consultations with over 30 stakeholders in Victoria Falls (Zimbabwe) and Livingstone (Zambia). The result is an online platform for further exchange of context-specific responses and the illumination of what is out there in relation to global political instruments. Such This way of bringing together researchers, practitioners, and decision-makers across sectors helps establishing a global-local dialogue across sectors while providing visibility and an opportunity for further financing of local projects. It is an innovative and brave example of connecting research and practice to envision a world, and importantly cities, that are more Child-Focused!

Lastly, we emphasize the generosity, openness and commitment of the people we had the privilege to connect and exchange ideas with. The breadth and depth of our explorations of participation and inclusion is testament to the dedication of the different people we spoke with.

- From a research perspective, what surprised you the most?

Among other interesting insights, we found that local governments and communities were willing to take part in the project, which we saw as an indication of the need to bridge the policy-research gap and support the planning of child-focused cities and spaces. This is important because there are limited literature and resources available to support governments and authorities in this regard.

Also, that the SDGs are not focussed on the rights and needs of children (for whom we are building this sustainable future), but rather include children under the broader umbrella of ‘for all’. Children have very specific needs (safety, accessibility, independent mobility, developmental opportunities) that need to be accounted for.

- What was the most significant change?

From the researchers' perspective, our own views on how local communitites regard child participation - Greenline Africa, a Zimbabwean local organisation for young people maintained that “involvement means that youth are owners of projects and not just beneficiaries, thus ‘nothing for us without us’”. Participation for them means that young people must be involved in projects concerning them from proposal level to implementation level.

But also the mindsets of people (Local Governments, Local Communities, Stakeholders involved). Realising that child-focused cities and spaces deliver far more benefit to the local community than ‘only space to play’. It is a key aspect of a sustainable community.

- How did the target community/country benefit from this project?

Apart from gaining insights into the possibilities of including child-focused spaces into their realities, we hope that people feel we can foreground their unique and rich knowledge and experience to echo and amplify the agenda for children’s rights, inclusion and participation internationally!

- Can you tell us the story about a person that this project impacted?

Ourselves! Our research team agree that as individuals, working in different fields of expertise, this project really impacted us all by enabling a trans-disciplinary environment for us to collaborate, think and plan. It has brought our individual disciplines into a broader context to understand different perspectives, sensitivities and possibilities.

- What was the biggest challenge in terms of connecting research and practice?

Among the many challenges to transform research into practical interventions, two main ones are language and funding. Research is conducted in English or any other official language. Yet, the practitioners and communities will be more conversant in local languages. For instance, the SDGs are rarely translated into local language that is palatable for local communities. Second, we observed that local authorities often fail to dedicate the financial resources needed to translate research findings into actionable deliverables and interventions that transform the community.

In this small-scale project, the relatively large impact is testament to the partnerships ICLD faciliatates with municipalities. We learned about the extreme pressures on people and resources which created precariousness around sustainable inclusion and participation. The greatest challenge is how to develop impact in a unequal and challenging global context.

- How can we continue with this change?

The next steps of CFCAF are under development, both to grow the knowledge deeper and wider. (note: Stay tuned via ICLD's channels).

- Why is it important to connect researchers with decision-makers and local government officials?

This connection is crucial to bridge the gap between research findings and actionable recommendations. Researchers play an important complementary role to build evidence-based findings, especially when municipalities have little or no set budgets dedicated to research on community issues. Bridging the gap between researchers and decision-makers has to be built at the conceptual stage to ensure ownership of the process and findings together with the decision-maker, potentially eliminating resistance from decision-makers. Buy-in from government officials is the greatest win for any research work done. Collaboration, participation, and co-production between research and local governments can make real and lasting impacts in supporting inclusion and participation for children.