Press release -

355 million-year-old footprints rewrite the history of backboned land animals

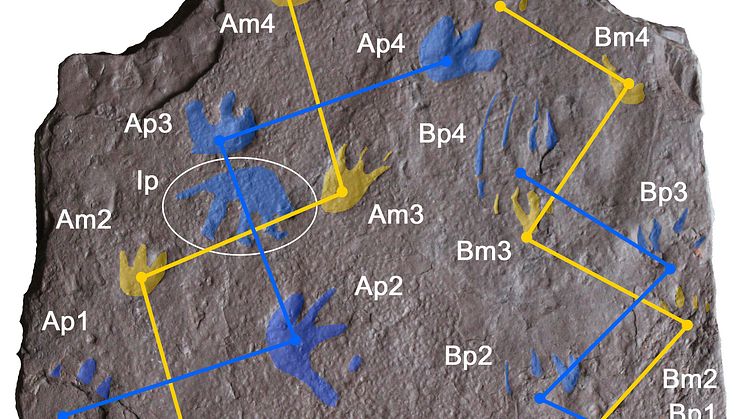

Newly discovered fossilised footprints with long toes and claws have been found in a rock slab from Australia. The discovery pushes the origin of reptiles back by 35 million years and overthrows the established evolutionary timeline of backboned land animals. The study, led by researchers at Uppsala University, has been published in the journal Nature.

A rock slab from Australia, about 355 million years old, is now changing the entire timeframe for the origin of backboned land animals, or ‘tetrapods’.

“The rock slab carries well-preserved footprints of long-toed feet with distinct claws. They are the oldest tracks of clawed feet in the world. It’s astounding that a single slab of rock, so small that one person can lift it, calls into question everything we thought we knew about the emergence of modern tetrapods,” says Per Ahlberg, professor at Uppsala University, who led the study.

Tracks of an early reptile

Tetrapods evolved from a group of fish that left the sea about 390 million years ago, during the Devonian period. They became the ancestors of all modern backboned land animals, i.e. amphibians and amniotes, a group that includes mammals, reptiles and birds. The oldest amniote fossils previously found come from the later part of the Carboniferous period and are about 320 million years old. The Australian sandstone slab, which is around 355 million years old, shows that reptiles already existed 35 million years earlier, at the beginning of the Carboniferous.

“When I first saw the rock slab, I was very surprised. After just a few seconds, I noticed that it bore clearly preserved claw marks. Claws are present in all early amniotes, but almost never in other groups of tetrapods. The combination of claw marks and the shape of the feet suggests that the tracks were made by a primitive reptile,” says Grzergorz Niedźwiedzki of Uppsala University, co-author of the study.

Reptile finds in Poland confirm picture

The researchers received further support for the interpretation that reptiles emerged at this time from newly discovered fossil reptile tracks from Poland, described in the article. They are not as old as the Australian rock slab, but substantially older than the previous oldest known examples.

Moving the origin of reptiles back in time changes the whole timeline of tetrapod evolution. Previously, scientists believed that the last common ancestor of amphibians and amniotes lived around 355 million years ago. But as the ancestor must be older than the oldest reptiles, that is now called into question.

Fossils and DNA redraw the evolutionary tree

By combining the dating of fossils with the DNA of living descendants, the researchers have tried to estimate when the last common ancestor of amphibians and amniotes might have lived. Their analysis shows that it was probably at the beginning of the latter part of the Devonian period. This period was previously thought to be populated exclusively by primitive fish-like tetrapods and transitional forms such as Tiktaalik.

“This means that advanced tetrapods were already living at a time when it was previously thought that only primitive ‘four-legged fish’ were dragging themselves along the shores and just beginning to explore the land. But perhaps we shouldn’t be surprised,” Ahlberg says. He continues:

“The Australian rock is about 50 cm wide and is currently the only tetrapod fossil of earliest Carboniferous age we have from the whole of Gondwana – a giant supercontinent that comprised Africa, South America, Antarctica, Australia and India. Who knows what other animals may have lived there?”

“The most interesting discoveries are yet to come. There is still so much to be found in the field. These footprints from Australia are just one example,” Niedźwiedzki concludes.

Publication

John A. Long, Grzegorz Niedźwiedzki, Jillian Garvey, Alice M. Clement, Aaron B. Camens, Craig A. Eury, John Eason and Per E. Ahlberg, 2025. Earliest amniote tracks recalibrate the timeline of tetrapod evolution. Nature.

Contact

Per Ahlberg, professor at the Department of Organismal Biology, Uppsala University.

Telephone: +4618-471 26 41

Email: per.Ahlberg@ebc.uu.se

Funding

The research was supported by the Tetrapod Origin project, funded by the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement no. 101019613), and The Australian Research Council.

Topics

Categories

Founded in 1477, Uppsala University is the oldest university in Sweden. With more than 50,000 students and 7,500 employees in Uppsala and Visby, we are a broad university with research in social sciences, humanities, technology, natural sciences, medicine and pharmacology. Our mission is to conduct education and research of the highest quality and relevance to society on a long-term basis. Uppsala University is regularly ranked among the world’s top universities. www.uu.se